Russ Meyer Biography

He was the cigar-chomping rebel of American cinema—a WWII combat cameraman turned master of sex, satire, and unapologetic pulp. This Russ Meyer biography isn’t just about a filmmaker—it’s about a man who bulldozed the rules, rewrote them in bold, and added a pair of double-Ds for good measure. For the man who likes his movies loud, his women fierce, and his stories untamed, Meyer wasn’t just behind the camera—he was a genre unto himself.

Built from Grit: The Rough-Cut Boyhood of Russ Meyer

(Timeframe: ~1922 – circa 1946)

👦 From Divorce to 8mm: The Rough-Cut Origins of Russ Meyer

Before the breasts, the B-movies, and the bad girls, Russell Albion Meyer was just a scrappy kid from San Leandro, California, born on March 21, 1922. His early life wasn’t paved with glamour. In fact, it was stitched together with grit, a single mother’s resolve, and a camera that would ignite a lifetime of obsession.

Russ’s father, a hard-edged local cop, walked out when Russ was still a young boy. The divorce left his mother, Lydia Lucinda Hauck, to raise him alone. She was a stern but fiercely intelligent German immigrant with a backbone of steel. And she knew one thing about her son: he was different. Obsessed. Restless. Always looking at the world through an invisible lens.

So, when Russ was just 14, his mother did something that would become legend—she pawned her wedding ring to buy him a movie camera. Not a toy. A real-deal 8mm camera. While most kids his age were playing baseball or chasing girls, Russ was chasing light, shadows, and motion.

🎥 Born to Shoot

From the moment he loaded his first roll of film, Russ Meyer was hooked. He recruited neighborhood kids to act in homemade silent shorts, often using exaggerated characters and dramatic angles, already channeling the over-the-top flair that would define his future work.

He was a one-man production crew—writing, shooting, editing, even building makeshift sets. He didn’t care for polished Hollywood fare. Instead, he gravitated toward the raw energy of early cinema pioneers like Sergei Eisenstein and D.W. Griffith, favoring bold visuals and primal emotion over pretty storytelling.

By the time he hit high school, Russ was known as “the camera guy.” He took photos for the school paper, made money on the side shooting portraits and posters, and occasionally convinced young women to pose in ways that would’ve made the principal faint. The seeds of “Meyer-style” cinema—strong women, sharp curves, and a lot of attitude—were already growing.

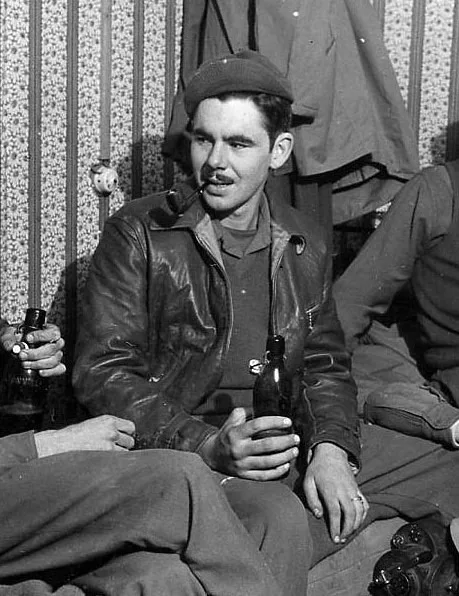

⚔️ War Zones & Lenses

When World War II broke out, Russ didn’t hesitate—he enlisted in the Army and landed a spot in General Patton’s 166th Signal Photographic Company, a combat cameraman unit that followed troops into battle, documenting the blood, sweat, and bullets.

This wasn’t studio lighting and dolly tracks. It was grenades, guts, and handheld film in war-torn Europe. Russ filmed everything from beach landings to liberation scenes. He saw death up close—and captured it with brutal honesty. Those years in the trenches didn’t just give him technical skill; they gave him a worldview. A raw, uncompromising vision of humanity that would later pulse through his most infamous films.

His war footage, still archived by the U.S. military, was considered some of the most intense and cinematic of its kind. Russ later claimed the war gave him two things: a respect for strong women (many of whom were survivors he met overseas) and a lifelong refusal to flinch.

🎥 Meyer’s Lens in Patton

- During WWII, Meyer served as a staff sergeant with Patton’s 166th Signal Photographic Company, part of General Patton’s 3rd Army

- His bravura camerawork—handheld, in the thick of battle—won praise from his superiors and was later woven into major motion pictures .

- Notably, footage he shot for the U.S. Army’s newsreel units ended up in the Oscar-winning short Eisenhower: True Glory (1945), as well as portions of the feature films The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and Patton (1970).

- His credit as a cinematographer in Patton is officially confirmed: he is listed among the film’s camera crew “Newsreel Unit #1”

🔥 A Young Rebel in the Making

Russ Meyer didn’t come from money. He didn’t have connections. What he had was an unshakable drive, a wicked sense of humor, and a camera that never stopped rolling. His childhood wasn’t sentimental—it was survival with a touch of style. And it shaped him into the kind of filmmaker who didn’t wait for permission.

Before he ever yelled “action,” Russ Meyer lived it—hard, fast, and through the lens of a mind built for more than just movies.

📅 Timeframe: 1922 – circa 1946

1945–1946: Returns from the war; his wartime footage is later used in The True Glory (1945), The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, and Patton (1970).

1922: Russ Meyer is born on March 21 in San Leandro, California.

~1936 (age 14): Receives his first 8mm film camera after his mother pawns her wedding ring.

1936–1940: Shoots amateur short films, photographs school events, and begins shaping his cinematic instincts.

1942–1945: Serves as a combat cameraman with Patton’s 166th Signal Photographic Company in WWII, filming battles across Europe.

📸 “From Combat to Curves”

(Timeframe: ~1946–1959)

🎬 From Foxholes to Photo Shoots: Russ Meyer Hits Hollywood

The war was over, but Russ Meyer still had his finger on the trigger—only now, it was the shutter release. Back in civilian clothes and loaded with combat experience, Meyer marched straight into the post-war American dream with one mission: to make pictures that punched.

And in late-1940s Hollywood, there was no shortage of targets.

📸 King of the Cheesecake Shot

Fresh out of the Army, Meyer started hustling as a still photographer. Not the glamorous studio jobs reserved for insiders—but gritty, freelance assignments that paid in cash and cigarettes. He shot everything from auto ads to publicity headshots. But where he really made his mark was in the booming world of “cheesecake” photography—the pin-up style that dripped with mid-century Americana and feminine allure.

He had a gift for capturing women not just as sex symbols, but as forces of nature. Strong, confident, dominant even—traits that would later define his cinematic heroines.

By the early 1950s, his work was getting noticed. Magazines like Modern Man, Gala, and Fling ran his photographs regularly. But it wasn’t just the T&A that set his work apart—it was the attitude. His models weren’t just posing, they were challenging the lens. Looking right into it like they were about to take control of the frame—and maybe you, too.

💋 A Star Is Bare: Eve Meyer

In 1952, Russ met Eve Turner, a stunning blonde model who would become both his wife and muse. She took the name Eve Meyer, and under Russ’s lens, she became a sensation.

Eve wasn’t just another pretty face. She had presence, charisma, and that same larger-than-life energy Russ craved in his images. She soon became a top pin-up model and even landed a spot as Playboy’s Playmate of the Month in June 1955. (Hugh Hefner, reportedly, had huge respect for Meyer’s eye behind the camera.)

Their partnership blurred every line—professional, personal, and artistic. And Eve would go on to star in several of Russ’s early films, becoming the first in a long line of powerful, voluptuous leading women in his cinematic universe.

🎞️ Cracking the Celluloid Ceiling

As the 1950s rolled into the ‘60s, Russ began growing restless behind the still camera. The war had shown him the thrill of motion, of narrative, of cinema as a weapon. He wanted more than frames—he wanted to tell stories. Dirty, dangerous, over-the-top stories full of sex, satire, and strong women.

He began experimenting with short films, learning how to stretch a dollar on set. He also made industrial films—dry but necessary work that gave him hands-on experience with editing, lighting, and directing.

Then in 1959, he took the plunge.

Using his own money, industry favors, and sheer willpower, Russ Meyer made his first feature film:

“The Immoral Mr. Teas”.

It cost less than $30,000 to make—and grossed over a million at the box office.

🔥 The Teas Breakthrough

The Immoral Mr. Teas was a revelation. It wasn’t porn, but it wasn’t innocent either. It walked the line with a smirk, showcasing nudity and slapstick in a way American audiences had never seen before. Russ had invented something new: the “nudie cutie.”

And Hollywood didn’t know what hit it.

📅 Timeframe: circa 1946 – 1959

- 1946: Returns from World War II and begins working as a freelance still photographer in Los Angeles.

- Late 1940s – early 1950s: Builds reputation shooting pin-up and “cheesecake” photography for magazines like Modern Man and Fling.

- 1952: Meets and marries model Eve Turner, who becomes his muse and frequent collaborator.

- Mid-1950s: Eve Meyer gains prominence as a top pin-up model and Playboy Playmate (June 1955).

- Late 1950s: Russ experiments with short films and industrial projects, gaining filmmaking experience.

- 1959: Releases his first feature film, The Immoral Mr. Teas, marking his official entry into feature filmmaking.

🔥 The Immoral Mr. Teas and the Birth of a Cult Legend

(Timeframe: 1959–1963)

In 1959, Russ Meyer dropped a bombshell on the conservative world of American cinema. With a shoestring budget of less than $30,000, he wrote, directed, and produced The Immoral Mr. Teas — a cheeky, groundbreaking “nudie cutie” that challenged the era’s strict boundaries on nudity and sexuality.

🎬 A Film That Flipped the Script

Forget Hollywood glitz—The Immoral Mr. Teas was raw, playful, and unapologetically risqué. The story? A meek guy who suddenly finds himself irresistibly attracted to nude women everywhere he goes. But Meyer’s genius wasn’t just in the nudity; it was in the tone—lighthearted, irreverent, and downright funny.

This was not smut; it was sex-positive satire before the phrase even existed.

💥 From Indie Flick to Box Office Smash

The film blew up. Word-of-mouth turned into wild success. Distributors couldn’t keep it on the shelves. Within a year, The Immoral Mr. Teas had grossed over a million dollars—an astonishing feat for a movie so small, so fringe, and so daring.

Hollywood took notice. But instead of welcoming Meyer with open arms, the mainstream turned a wary eye to his bold new genre. So Russ took the road less traveled—building his empire in the underground and drive-in circuits.

🍑 Bigger, Bolder, and More Badass

Fueled by his sudden success, Meyer doubled down. He knew what audiences craved: strong, voluptuous women with attitude, stories dripping in camp, humor, and unapologetic sex appeal.

His follow-up films — like Eve and the Handyman (1961) and Wild Gals of the Nakes West (1962) — ratcheted up the stakes, mixing bawdy comedy with his signature visuals of powerful female leads.

🎥 Europe in the Raw and the Cult of Excess

By 1963, Meyer’s style was unmistakable. He took audiences on wild rides through the seedy underbelly of Europe in Europe in the Raw (1963), a documentary-style exploration of nightlife and raw human desire.

The film wasn’t just about skin; it was about the edge of freedom and rebellion — themes Meyer had lived since his youth and wartime days.

🔥 The Making of a Maverick

From 1959 to 1963, Russ Meyer didn’t just make movies—he made a new kind of movie experience. He carved a niche that was part grindhouse, part erotica, and all attitude.

It was clear: Russ Meyer was no Hollywood player. He was a rebel with a camera, and he was just getting started.

📅 Timeframe: 1959 – 1963

1959: Releases his first feature film, The Immoral Mr. Teas, pioneering the “nudie cutie” genre; film becomes a surprise box office hit

1961: Directs Eve and the Handyman, continuing his formula of strong, sexy women and campy humor.

1962: Releases Wild Gals of the Nakes West further establishing his signature style of bawdy comedy and empowered female leads.

1963: Directs Europe in the Raw, a provocative documentary exploring Europe’s nightlife and underground scenes.

🚬 Faster, Hotter, Wilder: Russ Meyer’s Reign Begins

(Timeframe: 1964–1968)

By 1964, Russ Meyer wasn’t just pushing boundaries—he was stomping on them in high heels and a bullet bra. Hollywood still didn’t know what to make of him, but America’s back-alley theaters and drive-ins couldn’t get enough.

The counterculture was rising, the censors were slipping, and the world was hungry for something bold. Russ delivered exactly that—one buxom badass at a time.

💣 Lorna (1964): Sex, Sin, and Cinematic Muscle

Russ kicked off this new era with Lorna, his first serious attempt at blending raw sexuality with dramatic storytelling. Dubbed by Meyer himself as “the first rural gothic,” Lorna was part erotica, part backwoods tragedy—complete with rape, murder, and redemption.

Starring the statuesque Lorna Maitland, the film broke new ground. It had nudity, yes—but also emotion, tension, and an unmistakable moral edge. Meyer was no longer just winking from behind the camera. He was crafting full-blooded narratives—just with more curves and sweat than the Hollywood elite could handle.

And it worked. Lorna raked in money, outrage, and underground acclaim.

🔥 Mudhoney (1965): Meyer Goes Literary (Sort Of)

Next came Mudhoney, loosely inspired by Erskine Caldwell’s Southern-fried pulp. Shot in black and white and packed with lust, violence, and religious hypocrisy, the film flopped commercially—but Meyer considered it one of his finest.

Why? Because it showed he could do more than tease. Mudhoney was angry, experimental, and gritty—more Tennessee Williams than titillation. Critics didn’t get it. Meyer didn’t care.

💋 Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965): The Cult Classic

If Mr. Teas made him famous, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! made him immortal.

This was Meyer unchained: a black-and-white explosion of leather, vengeance, fast cars, and ferocious women with fists and figures that broke bones and box office records. Tura Satana, the film’s lead, became an icon—equal parts femme fatale, street fighter, and feminist legend.

It bombed in theaters but exploded later on the cult circuit, earning praise from Quentin Tarantino to John Waters. Decades later, it’s still one of the most revered exploitation films ever made.

🎞️ The 1966–68 Grindhouse Machine

Meyer was now in full control. He wrote, directed, edited, and often narrated his films—his thumbprint all over every frame.

- Motorpsycho! (1965): biker scum and desert revenge.

- Mondo Topless (1966): part documentary, part strip club fever dream.

- Common Law Cabin (1967) and Good Morning… and Goodbye! (1967): more nudity, more nihilism, more cinematic swagger.

He didn’t care about the mainstream. His films were made cheap, fast, and independently distributed. They were anti-Hollywood and pro-attitude—and the audience was loving it.

🏁 No Brakes, No Apologies

By 1968, Russ Meyer had gone from outsider to underground royalty. His films were still banned in some states and barely reviewed by critics, but they kept packing theaters.

What set him apart wasn’t just the sex—it was the style. His editing was rapid-fire. His compositions bold. His soundtracks pounding. He made exploitation art, and no one else even came close.

📅 Timeframe: 1964–1968

- 1964: Releases Lorna, his first blend of sexploitation and Southern melodrama.

- 1965: Directs Mudhoney and the now-legendary Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, the latter becoming one of the most iconic cult films of all time.

- 1966: Experiments with hybrid documentary form in Mondo Topless.

- 1967–68: Continues building his mythos with Common Law Cabin and Good Morning… and Goodbye!—films that mix surrealism, sensuality, and social critique.

🎥 From X to Fox: Russ Meyer Takes on the Studio System

(Timeframe: 1968–1970)

Russ Meyer had conquered the grindhouse, ruled the drive-ins, and built a cult following on sex, satire, and sheer cinematic bravado. But by the end of the ’60s, he did what no one expected:

He went legit.

Well, Meyer-legit. Which meant full-frontal anarchy—just with better cameras, a bigger budget, and the backing of a major Hollywood studio.

🔥 Vixen! (1968): The Breakthrough That Busted the Rules

It started with Vixen!, the film that finally made Russ Meyer a millionaire—and not just in reputation. Starring the fiery Erica Gavin as a nymphomaniac who seduces everything on two legs (including her brother-in-law and a Black militant), the film was pure provocation.

But Meyer wasn’t just out to shock. He was poking holes in racism, sexual repression, and middle-class morality—all while delivering his signature dose of wild women and sharp cuts.

The result? A $73,000 budget turned into over $8 million at the box office.

It was the first X-rated film to become a mainstream hit.

💼 The Call from the Big Leagues

Hollywood had finally stopped laughing. 20th Century Fox was watching—and they saw dollar signs. In the wake of the Easy Rider revolution, studios were desperate to capture the youth market. They didn’t need another John Ford. They needed a shock doctor. Someone who understood counterculture chaos.

They needed Russ Meyer.

Fox offered him something unheard of: total creative control over a major studio film. The only catch? He had to work from a rough outline for a sequel to Valley of the Dolls—the 1967 melodrama turned camp classic.

Russ agreed. But on one condition: he could bring in a screenwriter of his own choosing.

✍️ Enter Roger Ebert

That’s right—Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert. At the time, he was a rising star at the Chicago Sun-Times, known for his sharp mind and deep love of movies. Meyer admired his writing. Ebert, secretly fascinated by Meyer’s brand of erotic anarchy, said yes.

Together, they created something totally insane:

🎬 Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970): Sex, Rock & Shock Therapy

Forget a sequel. Beyond the Valley of the Dolls was a satirical explosion—a neon-lit trip through fame, drugs, exploitation, and death, with a killer soundtrack and a cast of unknowns (including Dolly Read).

It had everything:

- Sex and gender-fluid romance.

- LSD freakouts.

- Musical numbers.

- Murder.

- Nazis.

- A narrator who made no sense.

It was surreal, sleazy, and unapologetically brilliant.

Critics were baffled. Audiences? Obsessed.

Despite being slapped with an X rating and nearly banned, the film became an instant cult classic—and later, a respected entry in the Criterion Collection.

🤝 Meyer and Ebert: The Odd Couple

Ebert later called it “the best film Roger Ebert ever wrote.”

Meyer called Ebert “the smartest guy I’ve ever worked with.”

Their partnership defied logic—but it worked.

They would go on to write Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens and remained close until Meyer’s death. It was one of Hollywood’s strangest, most effective creative duos.

🎞️ Meyer Makes It… and Breaks It

Russ finally had the studio deal. The budget. The press. But he didn’t like the leash. After Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, Fox gave him two more pictures—The Seven Minutes (1971) flopped hard, and Meyer walked away from the majors for good.

Why? Because Meyer was never meant to play it safe. He was born to be a cinematic outlaw.

📅 Timeframe: 1968–1970

- 1968: Vixen! becomes the first X-rated box office hit in America.

- 1969: Hired by 20th Century Fox to direct Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

- 1970: Beyond the Valley of the Dolls premieres to shock, awe, and cult status; Meyer becomes a Hollywood renegade.

- 1971: Directs The Seven Minutes—a commercial misfire that ends his brief studio chapter.

🍑 Return of the King: Russ Meyer Unleashed

(Timeframe: 1971–1979)

Hollywood tried to contain him. They failed.

After his brief and chaotic detour with 20th Century Fox, Russ Meyer walked away from the studios, the critics, and the fake smiles. He didn’t just return to the underground—he returned to form, with more fury, more flesh, and total control.

This was Russ Meyer at full power.

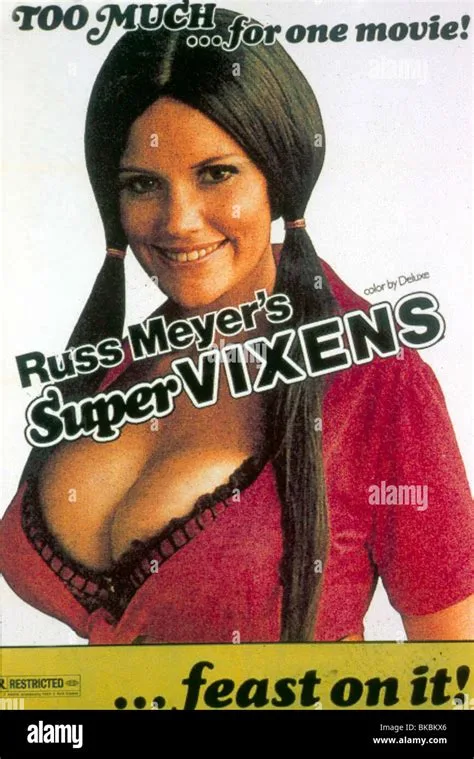

🎥 Supervixens (1975): Sex, Slapstick, and Savage Women

Back behind the camera on his own terms, Meyer unleashed Supervixens—a sun-drenched, surreal, and sex-soaked epic that plays like Looney Tunes meets Penthouse with a body count.

The story? A gas station attendant wrongly accused of murder runs from one busty maniac to another through America’s twisted back roads. It’s violent, absurd, erotic, and shot like a comic book dipped in acid.

Meyer pulled no punches. The film’s women were insane, empowered, and often lethal. The men? Hapless, horny buffoons. As usual, the power dynamic was flipped—and his audience loved it.

It was his biggest-budget independent production to date and a massive financial success.

🔥 Up! (1976): Hitler, Orgasms, and Full-Throttle Chaos

Meyer doubled down the following year with Up!, a film that opens with Adolf Hitler (yes, really) being murdered by a mystery woman during sex. That pretty much sets the tone.

What follows is part sex farce, part murder mystery, and part exercise in cinematic insanity. There’s a narrator in a tree, fight scenes that resemble wrestling matches, and dialogue that punches you in the face with camp and sleaze.

Up! was both a return to form and a spiritual successor to Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!—driven by violent women, outrageous characters, and a complete rejection of conventional storytelling.

✍️ Meyer & Ebert, Round Two

In 1979, Russ teamed up once again with Roger Ebert for what would be their most personal—and final—collaboration:

Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens.

A satire of small-town America and religious hypocrisy, the film starred Kitten Natividad—Meyer’s partner and muse at the time—and was soaked in gospel music, sleazy voice-overs, and relentless sexual absurdity.

Despite (or because of) its ridiculousness, it stands as one of Meyer’s most polished and self-aware films. It’s also arguably the last time he was truly firing on all cylinders.

🏠 The Independent Empire

Throughout the ‘70s, Meyer did what most of Hollywood couldn’t:

- He owned all his negatives.

- He distributed everything himself.

- He profited directly from the exploitation circuit.

While studios were getting eaten alive by bloated blockbusters, Meyer was laughing all the way to the bank—from a house he built with his own hands, stocked with his own editing gear, and lined with reels of forbidden film.

He didn’t need agents. He didn’t need approval.

He had an empire made of cleavage, reels, and cash.

📅 Timeframe: 1971–1979

- 1975: Supervixens premieres; it becomes a massive underground hit and showcases Meyer’s return to pure exploitation chaos.

- 1976: Releases Up!, one of his most surreal and controversial films.

- 1979: Collaborates with Roger Ebert on Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens, a final statement on sex, religion, and America.

- Throughout the 1970s: Russ Meyer thrives as a fully independent filmmaker, distributing his own films and maintaining financial and creative control.

🎞️ The Final Fade-Out: Sex, Silence & Legacy

(Timeframe: 1980–2004)

By the 1980s, Russ Meyer had done it all. He’d fought through war, flipped off Hollywood, and carved his name into the granite of grindhouse cinema. But time—like the tight curves he filmed—was not gentle.

Meyer didn’t go out with a bang. He faded like an old film reel, dusty and full of ghosts.

⚰️ The Decline of the Drive-In

By the early ’80s, the world Meyer thrived in—drive-ins, seedy theaters, and B-movie double bills—was vanishing. VHS and home video killed the wild west of low-budget cinema. The marketplace became crowded, the audiences splintered, and the thrill of exploitation wore thin.

Meyer attempted a few smaller projects, including the unfinished Foxy (which never saw release), and struggled to adapt to a world that had moved on. His style, once revolutionary, now felt like a relic to a generation saturated in softcore and desensitized by cable TV.

Russ never really changed. The world did.

💔 Love, Loss & Kitten

Meyer’s longtime companion, Kitten Natividad, was more than a star—she was the final muse. They lived together for years, their bond both romantic and artistic. But it was complicated.

As Meyer aged, his health declined, and so did the relationship. The wild parties stopped. The cameras went cold. In later interviews, Kitten recalled the loneliness that crept in, and the walls Meyer built around himself as the years stacked up.

🏠 Life in the Vault

By the ‘90s, Meyer had effectively retired. He lived alone in his home in the Hollywood Hills—part shrine, part editing bay, part fortress of old reels and sex memorabilia. His famous archive of 16mm film and photography was said to be one of the most extensive private collections in the U.S.

He didn’t give many interviews. But when he did, he was still Russ—proud, loud, and ready to name-drop “big bosoms and square jaws” like gospel.

Later Years & Final Work

In 2001, Meyer returned with Pandora Peaks, his final directorial project — a 72-minute direct-to-video film with no dialogue, featuring glamour model Pandora Peaks alongside Tundi, Candy Samples, and Leasha. The film showcases the women stripping and posing in various locations, interspersed with narration from Meyer and Peaks herself.

Pandora Peaks is also notable for incorporating segments from Meyer’s long-gestating but never completed autobiographical film, The Breast of Russ Meyer. Though more subdued than his earlier work, the film serves as a reflective coda to his career — a visually stylized farewell from a director whose vision remained uniquely his own until the very end.

🧠 The Mind Unravels

The early 2000s brought the cruelest twist of all: Alzheimer’s disease. The man who had once cut film with the precision of a surgeon was now slipping into silence. Friends and former collaborators described visits that were heartbreaking. He would forget names. Faces. Even the titles of his own films.

The razor wit dulled. The bawdy stories faded. And the lens finally went dark.

⚰️ The Death of a Rebel

Russ Meyer died on September 18, 2004, at the age of 82. He passed in his sleep at his home in the Hollywood Hills, the very house he built from the success of films nobody believed in except him.

There was no big funeral. No Hollywood eulogy. Just a handful of friends, lovers, and oddballs paying tribute to a man who had lived like no one else.

🎬 Meyer’s Legacy: Sleaze, Power & Cult Immortality

Meyer’s work never won an Oscar. He never got a star on the Walk of Fame. But what he created outlived all of that. His films—wild, sweaty, unfiltered—became cultural artifacts, studied in film schools and championed by renegade critics.

Quentin Tarantino called him a genius.

John Waters worshipped him.

Feminists debated him.

Cinephiles canonized him.

To this day, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! remains a totem of cinematic cool—referenced in fashion, music videos, even haute couture.

His unapologetic celebration of strong, sexual women—whether empowering, exploitative, or both—continues to ignite debate.

Love him or loathe him, Russ Meyer made movies like nobody else.

And he never asked for permission.

🗓️ Timeframe: 1980–2004

- 1980s: The decline of the grindhouse scene sidelines Meyer’s filmmaking.

- 1983–1990s: Attempts at comeback projects stall; Meyer retreats into semi-retirement.

- Late 1990s: Begins suffering from Alzheimer’s; public appearances cease.

- 2002: Release Pandora Peaks

- 2004: Dies at 82 in Hollywood, CA.

- Posthumous: His work gains scholarly attention; multiple retrospectives, Blu-ray restorations, and cult followings emerge worldwide.

✅ Final Cuts & Curves: The Last Legend of Russ Meyer

💃 The Queen of Curves: Kitten Natividad & Beyond

(Timeframe: 1965–2004)

Russ Meyer didn’t just film women—he immortalized them. His lens gave rise to an army of onscreen goddesses who weren’t just curves in motion—they were icons of power, vengeance, and sexual defiance. From the deadly Tura Satana in Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) to the voluptuous Kitten Natividad, Meyer’s women didn’t wait to be rescued—they rescued themselves, usually with a punch, a switchblade, or a machine gun.

🎞️ Kitten: More Than a Muse

By the mid-’70s, one woman stood above the rest: Kitten Natividad. Born in Mexico and raised in Texas, Kitten was a burlesque dancer with a magnetic presence. She met Meyer in the early 1970s and quickly became not just his star but his lover and collaborator. She narrated Up! (1976) and headlined Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens (1979)—two of his most sexually explicit, boundary-pushing films.

Off-screen, they were a powerhouse couple: lusty, loud, and inseparable. She matched Meyer’s bravado beat for beat, and her fearless performances helped define his late-period style—wilder, raunchier, and more unapologetic than ever.

“She wasn’t just the queen of curves,” Meyer once said, “she was the whole damn throne.”

🎥 Crafting the Meyer Formula

Meyer’s signature style was already legendary by then: whip-fast editing, jarring zooms, extreme close-ups, and a strange blend of narration that made even the sleaziest story sound profound. He didn’t just shoot sex—he shot it like a battlefield, with angles, sweat, and grit.

His budget might’ve been low, but the polish was pro. Every frame was under his thumb. He wrote, directed, shot, edited, and distributed his films himself—controlling the process like a battlefield general. He was, in essence, an army of one.

⚔️ Bans, Battles & Backlash

Meyer’s work wasn’t welcomed everywhere. Vixen! (1968) was banned in parts of Canada and the UK. Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970)—his major studio debut written with a young, untested Roger Ebert—received an X rating. But where the censors saw filth, Meyer saw fuel.

He never cowered to the moral police. If anything, controversy sold tickets—and he knew it.

“Every ban was just another billboard,” he famously quipped.

🎬 Sexploitation Meets Satire

To label Meyer’s work as pure smut misses the point. Beneath the busts and bullets, his films delivered sharp, campy satire. He lampooned American hypocrisy, conservative repression, and Hollywood’s sanitized fakery. Roger Ebert called him “the pop Fellini of sexploitation,” and for good reason.

His films had punchlines and power—sex as social rebellion, humor as shock therapy.

🔄 Beyond the Exploitation Label

Long before terms like “sex-positive” or “feminist subversion” were buzzwords, Meyer was staging wild, weaponized femininity front and center. Sure, his actresses were often undressed—but they were also unchained. They fought, they raged, they dominated the men around them.

Academics later reexamined Meyer’s legacy with new eyes—less about T&A, more about the raw, unfiltered celebration of women who took no shit and made no apologies.

💡 Influence: From Tarantino to MTV

Meyer’s touch is everywhere. You can see it in Kill Bill, Grindhouse, and any music video that throws a wink with a whip. Lady Gaga, Rob Zombie, and countless others borrowed his stylized aggression, outrageous costuming, and comic-book femininity.

His films became midnight staples. Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! is now cited as a feminist cult classic, celebrated by both drag queens and punk bands alike.

🛠 The Business Behind the Madness

Behind the camera, Russ Meyer was a control freak in the best way. After 1979, he pivoted hard to the home-video market—selling VHS and later DVD copies of his films out of his own office. No distributors, no studios, no compromises. He controlled his entire catalog like a vault, answering his own phones, processing orders, and printing packaging on his own dime.

In 2000, he self-published A Clean Breast, a massive three-volume autobiography full of wartime stories, behind-the-scenes chaos, and more bare-chested tributes than you can count. It was Meyer in book form: oversized, over-the-top, and completely unfiltered.

✅ The Final Cut

Russ Meyer died on September 18, 2004, at age 82 in Los Angeles, after battling complications from Alzheimer’s. But his legacy is anything but faded.

He was a renegade, a provocateur, and a master craftsman who treated the camera like a weapon and the screen like a war zone. He never begged for approval. He never toned it down. He made films that grabbed you by the collar and laughed while doing it.

Russ Meyer didn’t just break the rules—he rewrote them in cleavage and ink.

For the man who values freedom, brass, and a good punchline delivered by a six-foot bombshell in stilettos, Meyer remains pure, undistilled cinema gasoline.

🎯 If You’re Craving More

- Big Bosoms and Square Jaws by Jimmy McDonough – the definitive biography (archive.org)

- Russ Meyer: The Life and Films by David K. Frasier – annotated and picture‑heavy (biblio.com)

- A Clean Breast by Meyer himself – three‑volume memoir extravaganza

📚 Sources

- Wikipedia: Russ Meyer

- IMDB: Russ Meyer Filmography

- Psychotronic Video Guide

- Criterion Collection: Beyond the Valley of the Dolls

- RogerEbert.com on Russ Meyer

- Lydia R. Grace Blog Archive (Meyer Research)

- The New York Times Obituary

- Big Bosoms and Square Jaws (McDonough)

- University Press of Mississippi – Russ Meyer: Interviews

- A Clean Breast (Meyer)

- Archive.com lots of movies